John Lewis (pianist)

John Lewis | |

|---|---|

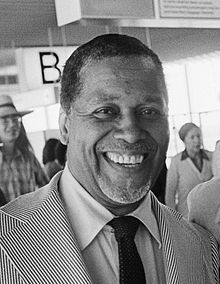

Lewis in 1977 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | John Aaron Lewis |

| Born | May 3, 1920 La Grange, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | March 29, 2001 (aged 80) New York City, U.S. |

| Genres | Jazz |

| Occupations |

|

| Instrument | Piano |

| Years active | 1940s–1990s |

| Formerly of | The Modern Jazz Quartet |

John Aaron Lewis (May 3, 1920 – March 29, 2001) was an American jazz pianist, composer and arranger, best known as the founder and musical director of the Modern Jazz Quartet.

Early life

[edit]John Lewis was born in La Grange, Illinois, and after his parents' divorce moved with his mother, a trained singer, to Albuquerque, New Mexico when he was two months old. She died from peritonitis when he was four and he was raised by his grandmother and great-grandmother.[1][2][3] He began learning classical music and piano at the age of seven.[4] His family was musical and had a family band that allowed him to play frequently and he also played in a Boy Scout music group.[5] Even though he learned piano by playing the classics, he was exposed to jazz from an early age because his aunt loved to dance and he would listen to the music she played.[5] After attending Albuquerque High School,[6] he then studied at the University of New Mexico,[4] where he led a small dance band that he formed[7] and double majored in Anthropology and Music.[5] His piano teacher at the university was Walter Keller, to whom he paid tribute on the title composition of the Modern Jazz Quartet's 1974 album In Memoriam.[8][9] Eventually, he decided not to pursue Anthropology because he was advised that careers from degrees in the subject did not pay well.[5] In 1942, Lewis entered the Army and played piano alongside Kenny Clarke, who influenced him to move to New York once their service was over.[10] Lewis moved to New York in 1945[10] to pursue his musical studies at the Manhattan School of Music and eventually graduated with a master's degree in music in 1953.[4] Although his move to New York turned his musical attention more towards jazz, he still frequently played and listened to classical works and composers such as Chopin, Bach and Beethoven.[5]

Jazz career

[edit]

Once Lewis moved to New York, Clarke introduced him to Dizzy Gillespie's bop-style big band. He successfully auditioned by playing a song called "Bright Lights" that he had written for the band he and Clarke played for in the Army.[11] The tune he originally played for Gillespie, renamed "Two Bass Hit", became an instant success.[12] Lewis composed, arranged and played piano for the band from 1946 until 1948 after the band made a concert tour of Europe.[4][11] When Lewis returned from the tour with Gillespie's band, he left it to work individually. Lewis was an accompanist for Charlie Parker and played on some of Parker's famous recordings, such as "Parker's Mood" (1948) and "Blues for Alice" (1951), but also collaborated with other prominent jazz artists such as Lester Young, Ella Fitzgerald and Illinois Jacquet.[4]

Lewis was also part of trumpeter Miles Davis's Birth of the Cool sessions. While in Europe, Lewis received letters from Davis urging him to come back to the United States and collaborate with him, Gil Evans, Gerry Mulligan and others on the second session of Birth of the Cool.[13] From when he returned to the U.S. in 1948 through 1949, Lewis joined Davis's nonet[13] and is considered "one of the more prolific arrangers with the 1949 Miles Davis Nonet".[14] For the Birth of the Cool sessions, Lewis arranged "S'il Vous Plait", "Rouge", "Move" and "Budo".[15]

Lewis, vibraphonist Milt Jackson, drummer Clarke and bassist Ray Brown had been the small group within the Gillespie big band,[16] and they frequently played their own short sets when the brass and reeds needed a break or even when Gillespie's band was not playing.[17] The small band received a lot of positive recognition and it led to the foursome forming a full-time working group, which they initially called the Milt Jackson Quartet in 1951 but in 1952 renamed the Modern Jazz Quartet.[4]

Modern Jazz Quartet

[edit]The Modern Jazz Quartet was formed out of the foursome's need for more freedom and complexity than Gillespie's big band, dance-intended sound allowed.[18] While Lewis wanted the MJQ to have more improvisational freedom, he also wanted to incorporate some classical elements and arrangements into his compositions.[14] Lewis noticed that the style of bebop had turned all focus towards the soloist, and Lewis, in his compositions for the MJQ, attempted to even out the periods of improvisation with periods that were distinctly arranged.[19] Lewis assumed the role of musical director from the start,[4] even though the group claimed not to have a leader.[20] It is commonly thought that "John Lewis, for reasons of his contributions to the band, was apparently the first among the equals".[21] Davis even once said that "John taught all of them, Milt couldn't read at all, and bassist Percy Heath hardly".[21] It was Lewis who elevated the group's collective talent because of his individual musical abilities.[21]

Lewis gradually transformed the group away from strictly 1940s bebop style, which served as a vehicle for an individual artist's improvisations, and instead oriented it toward a more refined, polished, chamber style of music.[22] Lewis's compositions for The Modern Jazz Quartet developed a "neoclassical style"[23] of jazz that combined the bebop style with "dynamic shading and dramatic pause more characteristic of jazz of the '20s and '30s".[14] Francis Davis, in his book In the Moment: Jazz in the 1980s, wrote that by "fashioning a group music in which the improvised chorus and all that surrounded it were of equal importance, Lewis performed a feat of magic only a handful of jazz writers, including Duke Ellington and Jelly Roll Morton, had ever pulled off—he reconciled the composer's belief in predetermination with the improviser's yen for free will".[19]

Lewis also made sure that the band was always dressed impeccably.[24] Lewis believed that it was important to dress the way that they came across in their music: polished, elegant and unique.[24] Lewis once said in an interview with Down Beat magazine: "My model for that was Duke Ellington. [His band] was the most elegant band I ever saw".[25]

From 1952 through 1974, he wrote and performed with and for the quartet.[4] Lewis's compositions were paramount in earning the MJQ a worldwide reputation for managing to make jazz mannered without cutting the swing out of the music.[26] Gunther Schuller for High Fidelity Magazine wrote:

It will not come as a surprise that the Quartet's growth has followed a line parallel to Lewis' own development as a composer. A study of his compositions from the early "Afternoon in Paris" to such recent pieces as "La Cantatrice" and "Piazza Navona" shows an increasing technical mastery and stylistic broadening. The wonder of his music is that the various influences upon his work—whether they be the fugal masterpieces of Bach, the folk-tinged music of Bartók, the clearly defined textures of Stravinsky's "Agon", or the deeply felt blues atmosphere that permeates all his music—these have all become synthesized into a thoroughly homogeneous personal idiom. That is why Lewis' music, though not radical in any sense, always sounds fresh and individual.[27]

During the same time period, Lewis held various other positions as well, including head of faculty for the summer sessions held at the Lenox School of Jazz in Lenox, Massachusetts from 1957 to 1960,[4] director of the annual Monterey Jazz Festival in California from 1958 to 1983,[10] and its musical consultant,[28] and "he formed the cooperative big band Orchestra U.S.A., which performed and recorded Third Stream compositions (1962–65)".[4] Orchestra U.S.A., along with all of Lewis's compositions in general, were very influential in developing "Third Stream" music, which was largely defined by the interweave between classical and jazz traditions.[10] He also formed the Jazz and Classical Music Society in 1955, which hosted concerts in Town Hall in New York City that assisted in this new genre of classically influenced jazz to increase in popularity.[29] Furthermore, Lewis was also commissioned to compose the score to the 1957 film Sait-On Jamais,[30] and his later film work included the scores to Odds Against Tomorrow (1959), A Milanese Story (1962), Derek Jarman's version of The Tempest (1979), and the TV movie Emmanuelle 4: Concealed Fantasy (1994). His score to Odds Against Tomorrow was released on both an original soundtrack album (UA 5061) and an interpretation album by the MJQ in 1959.

The MJQ disbanded in 1974 because Jackson felt that the band was not getting enough money for the level of prestige the quartet had in the music scene.[31] During this break, Lewis taught at the City College of New York and at Harvard University.[4] Lewis was also able to travel to Japan, where CBS commissioned his first solo piano album.[32] While in Japan, Lewis also collaborated with Hank Jones and Marian McPartland,[33] with whom he performed piano recitals on various occasions.[32]

In 1981, the Modern Jazz Quartet re-formed for a tour of Japan and the United States, although the group did not plan on performing regularly together again.[31] Since the MJQ was no longer his primary career, Lewis had time to form and play in a sextet called the John Lewis Group.[4] A few years later, in 1985, Lewis collaborated with Gary Giddins and Roberta Swann to form the American Jazz Orchestra.[4] Additionally, he continued to teach jazz piano to aspiring jazz students, which he had done throughout his career.[32] His teaching style involved making sure the student was fluent in "three basic forms: the blues, a ballad, and a piece that moves".[32] He continued teaching late into his life.

In 1989, Lewis was awarded an Honorary Doctorate from Berklee College of Music. He was recognized for his impact on jazz and his amazing career.[34]

In the 1990s, Lewis partook of various musical ventures, including participating in the Re-birth of the Cool sessions with Gerry Mulligan in 1992,[35] and "The Birth of the Third Stream" with Gunther Schuller, Charles Mingus and George Russell,[36] and recorded his final albums with Atlantic Records, Evolution and Evolution II, in 1999 and 2000 respectively.[37] He also continued playing sporadically with the MJQ until 1997, when the group permanently disbanded.[38] Lewis performed a final concert at Lincoln Center in New York City in January 2001.[37][39]

Death and personal life

[edit]Lewis died in New York City on March 29, 2001, as a result of prostate cancer.[1] He had been married for 39 years to harpsichordist and pianist Mirjana (née Vrbanić; 1936–2010), with whom he had a son and a daughter.[40][41]

Music

[edit]Style and influence

[edit]Leonard Feather's opinion of Lewis's work is representative of many other knowledgeable jazz listeners and critics:[42] "Completely self-sufficient and self-confident, he knows exactly what he wants from his musicians, his writing and his career and he achieves it with an unusual quiet firmness of manner, coupled with modesty and a complete indifference to critical reaction."[43] Lewis was not only this way with his music, but his personality exemplified these same qualities.[5]

Lewis, who was significantly influenced by the arranging style and carriage of Count Basie,[44] played with a tone quality that made listeners and critics feel as though every note was deliberate. Schuller remembered of Lewis at his memorial service that "he had a deep concern for every detail, every nuance in the essentials of music".[45] Lewis became associated with representing a modernized Basie style, exceptionally skilled at creating music that was spacious, powerful and yet, refined.[37] In an interview with Metronome magazine, Lewis himself said:

My ideals stem from what led to and became Count Basie's band of the '30s and '40s. This group produced an integration of ensemble playing which projected—and sounded like—the spontaneous playing of ideas which were the personal expression of each member of the band rather than the arrangers or composers. This band had some of the greatest jazz soloists exchanging and improvising ideas with and counter to the ensemble and the rhythm section, the whole permeated with the fold-blues element developed to a most exciting degree. I don't think it is possible to plan or make that kind of thing happen. It is a natural product and all we can do is reach and strive for it.[46]

It is considered, however, that Lewis was successful in exemplifying, in his arrangements and compositions, this skill that he admired.[47] Because of his classical training, in addition to his exposure to bebop, Lewis was able to combine the two disparate musical styles and refine jazz so that there was a "sheathing of bop's pointed anger in exchange for concert hall respectability".[48]

Lewis was also influenced by the improvisations of Lester Young on the saxophone.[49] Lewis had not been the first jazz pianist to be influenced by a horn player. Earl Hines in his early years looked to Louis Armstrong's improvisations for inspiration and Bud Powell looked to Charlie Parker.[49] Lewis also claims to have been influenced by Hines himself.[5]

Lewis was also heavily influenced by European classical music. Many of his compositions for the MJQ and his own personal compositions incorporated various classically European techniques such as fugue and counterpoint,[37] and the instrumentation he chose for his pieces, sometimes including a string orchestra.[50]

In the early 1980s, Lewis's influence came from the pianists he enjoyed listening to: Art Tatum, Hank Jones and Oscar Peterson.[32]

Piano style

[edit]Len Lyons depicts Lewis's piano, composition and personal style when he introduces Lewis in Lyons' book The Great Jazz Pianists: "Sitting straight-backed, jaw rigid, presiding over the glistening white keyboard of the grand piano, John Lewis clearly brooks no nonsense in his playing, indulges in no improvisational frivolity, and exhibits no breach of discipline nor any phrase that could be construed as formally incorrect. Lewis, of course, can swing, play soulful blues and emote through his instrument, but it is the swing and sweat of the concert hall, not of smoke-filled, noisy nightclubs." Although Lewis is considered to be a bebop pianist,[37][51] he is also considered to be one of the more conservative players.[4] Instead of emphasizing the intense, fast tempoed bebop style, his piano style was geared towards emphasizing jazz as an "expression of quiet conflict".[21] His piano style, bridging the gap between classical, bop, stride and blues, made him so "it was not unusual to hear him mentioned in the same breath with Morton, Ellington, and Monk".[52] On the piano, his improvisational style was primarily quiet and gentle and understated.[4] Lewis once advised three saxophonists who were improvising on one of his original compositions: "You have to put yourself at the service of the melody.... Your solos should expand the melody or contract it".[53] This was how he approached his solos as well. He proved in his solos that taking a "simple and straightforward... approach to a melody could... put [musicians] in touch with such complexities of feeling",[53] which the audience appreciated just as much as the musicians themselves.[53]

His accompaniment for other musicians' solos was just as delicate.[4] Thomas Owens describes his accompaniment style by noting that "rather than comping—punctuating the melody with irregularly placed chords—he often played simple counter-melodies in octaves which combined with the solo and bass parts to form a polyphonic texture".[4]

Compositions and arrangements

[edit]Similarly to his personal piano playing style, Lewis was drawn in his compositions to minimalism and simplicity.[44] Many of his compositions were based on motifs and relied on few chord progressions.[54] Francis Davis comments: "I think too, that the same conservative lust for simplicity of forms that draws Lewis to the Renaissance and the Baroque draws him inevitably to the blues, another form of music permitting endless variation only within the logic of rigid boundaries".[55]

His compositions were influenced by 18th-century melodies and harmonies,[4] but also showed an advanced understanding of the "secrets of tension and release, the tenets of dynamic shading and dramatic pause"[53] that was reminiscent of classic arrangements by Basie and Ellington in the early swing era. This combining of techniques led to Lewis becoming a pioneer in Third Stream Jazz, which was combined classical, European practices with jazz's improvisational and big-band characteristics.[4]

Lewis, in his compositions, experimented with writing fugues[56] and incorporating classical instrumentation.[18] An article in The New York Times wrote that "His new pieces and reworkings of older pieces are designed to interweave string orchestra and jazz quartet as equals".[57] High Fidelity magazine wrote that his "works not only show a firm control of the compositional medium, but tackle in a fresh way the complex problem of improvisation with composed frameworks".[27]

Thomas Owen believes that "[Lewis'] best pieces for the MJQ are 'Django', the ballet suite The Comedy (1962, Atl.), and especially the four pieces 'Versailles', 'Three Windows', 'Vendome' and 'Concorde'... combine fugal imitation and non-imitative polyphonic jazz in highly effective ways."[4]

Discography

[edit]As leader/co-leader

[edit]| Date recorded | Title | Label | Year released | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1955–03 | The Modern Jazz Society Presents a Concert of Contemporary Music | Norgran | 1956 | |

| 1956–02 | Grand Encounter | Pacific Jazz | 1956 | with Bill Perkins, Jim Hall, Percy Heath & Chico Hamilton |

| 1956–12 | Afternoon in Paris | Atlantic | 1957 | with Sacha Distel |

| 1956–07, 1957–02, 1957–08 |

The John Lewis Piano | Atlantic | 1958 | |

| 1958–02 | European Windows | RCA Victor | 1958 | |

| 1959–05 | Improvised Meditations and Excursions | Atlantic | 1959 | Trio, with Percy Heath (bass), Connie Kay (drums) |

| 1959–07 | Odds Against Tomorrow (Original Music From The Motion Picture Soundtrack) | United Artists | 1959 | Film score of Odds Against Tomorrow (1959) |

| 1960–02 | The Golden Striker | Atlantic | 1960 | |

| 1960–07, 1960–09 |

The Wonderful World of Jazz | Atlantic | 1961 | |

| 1960–12 | Jazz Abstractions | Atlantic | 1961 | With Eric Dolphy and Robert Di Domenica (flute), Eddie Costa (vibraphone), Bill Evans (piano), Jim Hall (guitar), Scott LaFaro and George Duvivier (bass), Sticks Evans (drume), Charles Libove and Roland Vamos (violin), Harry Zaratzian and Joseph Tekula (cello) |

| 1961–03 | Original Sin | Atlantic | 1961 | With Orchestra Sinfonica |

| 1962? | A Milanese Story | Atlantic | 1962 | With Bobby Jaspar (flute), Rebè Thomas (guitar), Giovanni Tommaso and Joszef Paradi (bass), Buster Smith (drums), Giulio Franzetti and Enzo Porta (violin), Tito Riccardi (viola), Alfredo Riccardi (cello); soundtrack |

| 1962–07 | European Encounter | Atlantic | 1962 | with Svend Asmussen |

| 1962–07 | Animal Dance | Atlantic | 1964 | With Albert Mangelsdorff (trombone), Karl Theodor Geier (bass), Silvije Glojnaric (drums) |

| 1960–09, 1962–05, 1962–10 |

Essence | Atlantic | 1965 | music composed and arranged by Gary McFarland |

| 1975? | P.O.V. | Columbia | 1975 | With Harold Jones (flute), Gerald Tarack (violin), Fortunato Arico (cello), Richard Davis (bass), Mel Lewis (drums, percussion) |

| 1976 | Statements and Sketches for Development | CBS/Sony | 1976 | Solo piano |

| 1976 | Helen Merrill/John Lewis | Mercury | 1977 | co-led by Helen Merrill (vocals) with Hubert Laws (flute), Richard Davis (bass), Connie Kay (drums) |

| 1976 | Sensitive Scenery | CBS/Sony | 1977 | Trio, with Michael Moore (bass), Connie Kay (drums) |

| 1978? | Mirjana | Ahead | 1978 | With Christian Escoudé (guitar), George Duvivier (bass), Oliver Jackson (drums) |

| 1979 | An Evening with Two Grand Pianos | Little David | 1979 | Duo, with Hank Jones (piano)[58] |

| 1979 | Piano Play House | Toshiba | 1979 | With Hank Jones, George Duvivier (bass), Shelly Manne (drums) |

| 1981 | Duo | Toshiba EMI/Eastworld | 1981 | with Lew Tabackin |

| 1982 | Kansas City Breaks | Finesse | 1982 | |

| 1982 | Slavic Smile | RVC/Baystate | 1983 | As The New Quartet (with Bobby Hutcherson (vibraphone), Marc Johnson (bass), Connie Kay (drums)) |

| 1984 | J.S. Bach Preludes and Fugues from the Well-tempered Clavier Book 1 | Philips | 1985 | With Joel Lester (violin), Lois Martin (viola), Howard Collins (guitar), Marc Johnson (bass) |

| 1986? | The Bridge Game aka J.S. Bach Preludes and Fugues from the Well-tempered Clavier Book 1, Vol. 2 | Philips | 1986 | With Joel Lester (violin), Lois Martin and Scott Nickrenz (viola), Howard Collins (guitar), Marc Johnson (bass) |

| 1987? | The Chess Game Part 1 | Philips | 1987 | With Mirjana Lewis (harpsichord); based on J.S. Bach's Goldberg Variations |

| 1987 | The Chess Game Part 2 | Philips | 1987 | With Mirjana Lewis (harpsichord); based on J.S. Bach's Goldberg Variations |

| 1988 | J.S. Bach Preludes and Fugues from the Well-tempered Clavier Book 1, Vol. 3 | Philips | 1989 | With Howard Collins (guitar), Marc Johnson (bass) |

| 1989 | J.S. Bach Preludes and Fugues from the Well-tempered Clavier Book 1, Vol. 4 | Philips | 1990 | With Anahid Ajemian (violin), Robert Dan (viola), Howard Collins (guitar), Marc Johnson (bass) |

| 1990 | Private Concert | EmArcy | 1991 | Solo piano; in concert |

| 1999 | Evolution | Atlantic | 1999 | Solo piano[59] |

| 2000 | Evolution II | Atlantic | 2001 | Six tracks quartet with Howard Collins (guitar), Marc Johnson (bass), Lewis Nash (drums); four tracks quartet with Howard Alden (guitar), George Mraz (bass), Nash (drums)[60][61][62] |

With the Modern Jazz Quartet

[edit]- The Modern Jazz Quartet with Milt Jackson, Percy Heath, John Lewis, Kenny Clarke (1953, Prestige 160)

- The Modern Jazz Quartet (1955, Prestige 170)

- Concorde (1955, Prestige 7005)

- Fontessa (1956, Atlantic 1231)

- Django (1956, Prestige 7057)

- The Modern Jazz Quartet (Atlantic, 1957)

- The Modern Jazz Quartet Plays No Sun in Venice (Atlantic, 1958)

- Third Stream Music (1957, 1959–60, Atlantic. 1345) including "Sketch for Double String Quartet" (1959)

- The Modern Jazz Quartet and the Oscar Peterson Trio at the Opera House (Verve, 1957)

- The Modern Jazz Quartet at Music Inn Volume 2 (Atlantic, 1958)

- Music from Odds Against Tomorrow (United Artists, 1959) – film soundtrack

- Pyramid (Atlantic, 1960)

- European Concert (Atlantic, 1960 [1962])

- Dedicated to Connie (Atlantic, 1960 [1995])

- The Modern Jazz Quartet & Orchestra (Atlantic, 1960)

- The Comedy (1962, Atlantic 1390)

- Lonely Woman (Atlantic, 1962)

- A Quartet is a Quartet is a Quartet (1963, Atlantic 1420)

- Collaboration (Atlantic, 1964) – with Laurindo Almeida

- The Modern Jazz Quartet Plays George Gershwin's Porgy and Bess (Atlantic, 1964–65)

- Jazz Dialogue (Atlantic, 1965) with the All-Star Jazz Band

- Concert in Japan '66 (Atlantic [Japan], 1966)

- Blues at Carnegie Hall (Atlantic, 1966)

- Place Vendôme (Philips, 1966) – with The Swingle Singers

- Under the Jasmin Tree (Apple, 1968)

- Space (Apple, 1969)

- Plastic Dreams (Atlantic, 1971)

- The Only Recorded Performance of Paul Desmond With The Modern Jazz Quartet (Finesse/Columbia, 1971 [1981]) – with Paul Desmond

- The Legendary Profile (Atlantic, 1972)

- In Memoriam (Little David, 1973)

- Blues on Bach (Atlantic, 1973)

- The Last Concert (Atlantic, 1974)

- Reunion at Budokan 1981 (Pablo, 1981)

- Together Again: Live at the Montreux Jazz Festival '82 (Pablo, 1982)

- Echoes (Pablo, 1984)

- Topsy: This One's for Basie (Pablo, 1985)

- Three Windows (Atlantic, 1987)

- For Ellington (East-West, 1988)

- MJQ & Friends: A 40th Anniversary Celebration (Atlantic, 1992–93)

As sideman

[edit]With Dizzy Gillespie

- The Bop Session (Sonet, 1975) – also with Sonny Stitt, Hank Jones, Percy Heath and Max Roach

- The Complete RCA Victor Recordings (Bluebird, 1995) – rec. 1937–1949

With Charlie Parker

- The Genius of Charlie Parker (1945–8, Savoy MG 12009 [1956])

- "Parker's Mood" (1948)

- Charlie Parker (1951–53, Clef 287)

- "Blues for Alice" (1951)

With others

- Clifford Brown, Memorial Album (Blue Note, 1953 [1956]) – contains New Star on the Horizon

- Ruth Brown, Ruth Brown (Atlantic, 1957)

- Benny Carter, Central City Sketches (MusicMasters, 1987)

- Miles Davis, The Complete Birth of the Cool (1948–50, Capitol Jazz)

- Milt Jackson, Ballads & Blues (Atlantic, 1956)

- J. J. Johnson, Stitt Plays Bird (Atlantic, 1964)

- Joe Newman, I Feel Like a Newman (Storyville, 1956)

- Sonny Rollins, Sonny Rollins at Music Inn (MetroJazz, 1958)

- Sonny Stitt, Sonny Stitt/Bud Powell/J. J. Johnson (Prestige, 1949 [1956])

- Barney Wilen, Jazz Sur Seine (Philips, 1958 [2000])

Contributions

- Orchestra U.S.A. (Colpix, 1963) – leader

- Bill Evans: A Tribute (Palo Alto, 1982) – performs "I'll Remember April"

- The Jazztet and John Lewis (Argo, 1961) – as composer and arranger

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Thurber, Jon (March 31, 2001). "John Lewis; Led the Modern Jazz Quartet". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 4, 2024.

- ^ Hightower, Laura (2004). "John Lewis". Contemporary Musicians. Gale. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ^ Lewis, John; Quinn, Bill. "John Lewis Interview Part 1". Howard University. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Owens, Thomas (October 31, 2001). "John Lewis". New Grove Music Online.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lyons, p. 77.

- ^ Steinberg, David (April 3, 2001). "Jazz Pianist John Lewis Dies at 80". Albuquerque Journal. Retrieved July 25, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Giddins, p. 378.

- ^ Giddins, p. 398.

- ^ "Albuquerque Celebrates its Own Jazz Icon". Weekly Alibi. July 7, 2016. Archived from the original on October 19, 2019. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Lyons, p. 76.

- ^ a b Korall, Burt (2002). Drummin' Men: The Heartbeat of Jazz The Bebop Years. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 81–82. ISBN 0-19-514812-6.

- ^ Giddins, p. 379.

- ^ a b Lyons, p. 78.

- ^ a b c Davis, p. 228.

- ^ Sultanof, Jeff. "The Dozens: The Birth of the Cool" Archived 2008-09-24 at the Wayback Machine. Jazz.com.

- ^ This practice of having small groups within the big band began in 1935 when Benny Goodman had a trio in his band that would play when the arrangers and other musicians in his band needed a break. Since that time, it became common for big bands to have smaller groups within (Giddins, p. 378).

- ^ Lyons, p. 79.

- ^ a b Giddins, p. 380.

- ^ a b Davis, p. 229.

- ^ Giddins, p. 383.

- ^ a b c d Idonije, Benson (October 19, 2009). "Lewis and The Modern Jazz Quartet". The Guardian Life Magazine.

- ^ Giddins, pp. 379–381.

- ^ Williams, Richard (2009). The Blue Moment. W. W. Norton & Company, p. 5, ISBN 0571245072.

- ^ a b Giddins, p. 382.

- ^ Bourne, Michael (January 1992). "Bop Baroque the Blues: Modern Jazz Quartet," Down Beat, pp. 20–25.

- ^ Giddins, p. 387.

- ^ a b Schuller, p. 56.

- ^ Schuller, p. 135.

- ^ Schuller, p. 134.

- ^ Schuller, p. 195.

- ^ a b Lyons, pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b c d e Lyons, p. 80.

- ^ He met Marian McPartland while teaching at Harvard (Lyons, p. 80).

- ^ Gitler, Ira (April 2007). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199886401.

- ^ Stewart, Zan (June 18, 1992). "Mulligan Presides Over Rebirth of Cool: 'This Is the Sound We Were Striving For,' Says Veteran Saxophonist, Who Plays in Newport on Friday", Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Ramsey, Doug (January 1997). "Jazz Reviews: The Birth of the Third StreamGunther Schuller/John Lewis/Jimmy Giuffre/J. J. Johnson/George Russell/Charles Mingus" by Doug Ramsey. JazzTimes.

- ^ a b c d e John Lewis Archived 2012-06-20 at the Wayback Machine. All About Jazz.

- ^ Voce, Steve (April 30, 2005). "Percy Heath". The Independent. Archived from the original on June 13, 2022. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- ^ Keepnews, Peter (March 31, 2001). "John Lewis, 80, Pianist, Composer and Creator of the Modern Jazz Quartet, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ Fordham, John (April 2, 2001). "Obituary: John Lewis". The Guardian. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ^ "Paid Notice: Deaths: Leiis, Mirjana". The New York Times. July 28, 2010. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ Originally from Encyclopedia of Jazz 1960 edition (Lyons, p. 76).

- ^ Lyons, pp. 76–77.

- ^ a b Giddins, p. 377.

- ^ Ratliff, Ben (April 19, 2001). "Recalling the Gentle Elegance of John Lewis, Jazzman", The New York Times.

- ^ Giddins, p. 388.

- ^ Davis, p. 230.

- ^ Davis, p. 227.

- ^ a b Silver, Horace; Philip Pastras, and Joe Zawinul (2006). Let's Get to the Nitty Gritty: The Autobiography of Horace Silver. Berkeley, Calif. [u.a.: University of California Press, p. 51, ISBN 0520253922.

- ^ Davis, p. 231.

- ^ He played with many of the great bebop players such as Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Sonny Rollins.

- ^ Davis, p. 233.

- ^ a b c d Davis, p. 234.

- ^ Giddins, p. 391.

- ^ Davis, p. 232.

- ^ He appreciated fugues for their use of counterpoint in jazz (Giddins, p. 380).

- ^ Pareles, Jon (June 23, 1987). "The Modern Jazz Quartet" The New York Times.

- ^ Yanow, Scott. "John Lewis: Evening with Two Grand Pianos". AllMusic. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- ^ Anderson, Rick. "John Lewis: Evolution". AllMusic. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- ^ Ramsey, Doug (March 1, 2001). "John Lewis: Evolution II". JazzTimes. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- ^ Jolley, Craig (May 1, 2001). "John Lewis: Evolution II". allaboutjazz.com. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- ^ Henerson, Alex. "John Lewis: Evolution II". AllMusic. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

References

[edit]- Davis, Francis (1986). In The Moment: Jazz in the 1980s. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195040902.

- Giddins, Gary (1998). Visions of Jazz: The First Century. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195132416.

- Lyons, Len (1983). The Great Jazz Pianists. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306803437.

Further reading

[edit]- Lalo, Thierry (1991). John Lewis (in French). Editions du Limon. ISBN 978-2907224222.

- Coady, Christopher (2016). John Lewis and the Challenge of 'Real' Black Music. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472122264.

External links

[edit]- JAZCLASS – John Lewis and the MJQ

- Lewis interviewed by Bill Quinn in the Howard University Jazz Oral History Project

- John Lewis at IMDb

- African-American jazz composers

- African-American jazz pianists

- American jazz educators

- 1920 births

- 2001 deaths

- Jazz musicians from New York City

- Jazz musicians from New Mexico

- Musicians from Albuquerque, New Mexico

- Jazz musicians from Illinois

- People from La Grange, Illinois

- Third stream pianists

- City College of New York faculty

- Harvard University faculty

- University of New Mexico alumni

- Manhattan School of Music alumni

- Deaths from prostate cancer in New York (state)

- 20th-century American jazz composers

- American jazz pianists

- American male jazz pianists

- 20th-century American pianists

- American male jazz composers

- Modern Jazz Quartet members

- Orchestra U.S.A. members

- 20th-century American male musicians

- 20th-century African-American musicians

- Albuquerque High School alumni

- DownBeat Jazz Hall of Fame members